The Interview: Monica Ballus

Issue 96 / Thu 15th Dec, 2022

The Arctic Circle is a destination that, for most, is a distant thought. After all, who would want to go kiting in -30°C?! Well, we found someone who did: Monica (Nika) Ballús. In this interview, we find out all about Nika's incredible experience in Lapland...

Nika, what sparked the idea of this incredible snowkiting expedition?

I was still in my hospital bed when I knew I needed a goal - something to look forward to so I could feel alive again. I wanted a challenge that would be physical, mental, and compatible with my way of life: exploring, blending into the environment, and moving with the force of nature. Being born in sunny Barcelona and Brazilian by heart, planning an expedition in the cold seemed challenging enough! But this is why I love kitesurfing. It is my tool to explore, to feel free.

Tell us more about the injury that put you in the hospital... What happened?

In September 2019, I was ready to embark on what I believed would be the greatest challenge of my life so far: I wanted to become the first person to traverse the open seas from Mallorca to Barcelona on a kite - alone. The day before departure, I rode my motorbike home when an animal crossed in front of me. I managed to avoid it but crashed into a wall instead.

I had over 15 broken bones and a total reconstruction of my left foot (they used my thigh to rebuild my foot). I spent almost a year in the hospital and rehab centre, living in a wheelchair while learning how to walk again. I named my new left heel Whakatau, after a Maori warrior, hoping it would become my new adventure partner. I have no sensitivity in Whakatau, which means my proprioception is not as good, and I can injure myself without noticing. Still today, Whakatau is "oversized", and I cannot wear "normal" shoes; I have to cut all my shoes, and you can generally find me wearing two different shoes.

How did this affect your ability to kite?

For a long time, I could not walk, so kiting was just a distant goal but the one that would get me up every day. I learned to sit ski on the snow and wanted to try with the kite when the pandemic hit. Later, about one year after the accident, I felt ready to try kiting again, so I drove 5 hours from Switzerland to the South of France on a day with a great forecast and gave it a shot. I wore a neoprene shoe on my left foot with an extra insole for protection, and it worked. That's what I still do today. Feeling the wind on my face again and flying over the water was the best feeling ever!

What made you choose Lapland?

Lapland has always appealed to me for the purity and strength I could sense from pictures. But, through all the beautiful images on Instagram or in photo books, I could see another reality behind these landscapes, one of harsh and rapidly changing weather. It is a snow "desert" shaped by its brutal storms and extreme temperatures - with small rounded hills, leafless tree forests, frozen lakes and rivers separated by steep canyons. That is the real Lapland, and one must experience it fully to truly know the place.

How did you prepare for this massive challenge?

I approach every challenge by first asking two key questions: What can I do? And who can help me?

I knew all the "sweat equity" was on my side. But I also knew that when I started thinking about the expedition, I could still barely walk. I had never slept in a tent in the snow or experienced freezing temperatures for an extended period. I knew the secret would lay in building the right support team around me.

I reached out to fellow adventurers like Alex Satori, Finnish locals with kitesurfing experience (Mika Bjorkmann and Lappis Kite School), doctors with expertise in cold expeditions (Louis Marxer from GRIMM in Switzerland) and even local police and rescue officers. I was lucky to find amazing people along the way that let me pick their brains, help double check my list of equipment and even lend me some equipment for the expedition. With very little time to test the equipment in real conditions, I relied mainly on their intel and my experience in handling risky situations.

The route you chose had never been explored in full - how did you feel getting ready to go into the unknown?

I planned to leave from Kilpisjarvi, a small fishermen's village in northern Finland, and head East into the Kasivarren wilderness area. I would follow a cross-country ski route for the first day. After that, I expected things to get real as I went deeper into the wilderness towards the desert border with Norway, from where I had almost no information and the maps were not very precise.

The navigation in the Norwegian part was very tricky, as I passed countless reindeer fences, rivers, forests and canyons, and even a telephone line I managed to kite under! But my main concern was finding unkiteable forests with soft, deep snow and the Reisa Canyon because I needed to learn how to walk uphill with a 70 kg sled. That, indeed, was exhausting!

Considering the difficult terrain and arctic weather, why did you decide to do this journey alone?

Come on... who would be crazy enough to embark on this kind of adventure with me, especially right out of the hospital, not knowing how Whakatau would react?! More seriously, after over a year in the hospital where I needed help for everything, I felt the need to prove to myself that I could be independent, connect with the new version of myself, assess my new limitations and really just feel how far I could go. I wanted to be in a place where I would own my successes and my mistakes and have no choice but to get myself out of whatever troubles I'd get myself into.

Which kites did you choose, and why?

When choosing the kites, my criteria were simple: safe, light, robust and performant. So, I packed a full quiver of GIN Shaman's for the trip: 4, 6, 9, and 12m with 3 bars, though I should have brought 4 bars. The Shaman 3 is a single skin kite specially designed by GIN Kiteboarding for mountain kiting. Single skins generate a lot of power in relation to their area. Therefore, you can fly a smaller and hence more agile kite than usual. Single skins are also lighter, and you can get them in the air with virtually no wind.

What happened when you first set out on this expedition?

I started in Kilpisjarvi, a small fishing village close to the Three Nations' Border Point. Here, locals are incredibly welcoming. A huge storm was expected on the day I had planned to leave, and they didn't let me go. They welcomed me into their homes, saying, "nobody stays outside during a storm".

When I eventually got going, it was like being on the starting line of a race: I knew all the work had been done before. It was time to go out and enjoy myself. I had no idea how Whakatau would react to long hours of walking and such extreme temperatures, so I tried not to obsess about sticking to my plan of completing the full traverse. Ultimately, it was hard not to put pressure on succeeding, mainly for the people who had trusted and supported me; I did not want to let them down!

How long was the journey? How did you occupy your thoughts during all of this time alone?

The journey was ten days, fully unsupported. During this kind of expedition, you are in problem-solving mode all the time, so there is not that much time to think about many things other than moving forward, trying to optimise the route based on the forecast, and staying warm and hydrated. It's literally MOVE. WARM UP. EAT. SLEEP. REPEAT and anything that gets in the way of any of these four things becomes an urgent and important issue to solve and requires all the focus.

Did you encounter any other adventurers along the way? Did you ever wish for a companion?

I met some skiers and fishermen at the beginning and, at the very end, in the more frequented parts of Finland and Norway but saw no one for most of the traverse. I enjoyed having time to reconnect with myself, and I felt the need to do this expedition alone. I will not lie; there were times when I wished I had an adventure partner, someone to bounce ideas back, double check if we were on the right track, someone I could rely on to have each other's back and help each other to pull the heavy sleds uphill or get each other out of the snow holes. But this perfect partner is hard to find. Maybe for the next one?

At any point, did you think you might not be able to accomplish your goal? Did you have a backup plan in place to get assistance if you couldn't?

On day 6, my fuel canister leaked, and I lost almost all my fuel. Without fuel, I cannot eat, drink or heat myself. I had only 2-3 days of fuel remaining, and I had to plan a new exit route and hope for some wind as it was no longer possible for me to walk out. That was pretty scary.

I had a support team that helped me with the weather forecast, communication and safety. Only one person in the team knew about the fuel leak and was monitoring my advancement towards the new exit point. I didn't know at the time, but he had already reached out to local forest guards in case I needed a rescue. I felt my support team was even more eager than me to have me complete that first solo traverse! I knew I was in good hands and was lucky I could focus 100% on giving it all to try to make it out safely.

What else went wrong during the journey?!

So many things! The funny thing is that everything that crossed my mind that could have gone wrong eventually did. On day 2, I got locked inside a small hut due to a snowstorm blocking the door from the outside. On day 3, I made a mistake reading the compass and ended up way south compared to where I had planned on crossing the Norwegian border. The next day, I decided to cross where I was, but the snow was deep. At some point, I was buried waist-deep with skis on, attached to my sled, and in the middle of the frozen river I was crossing. My biggest fear was getting wet, and I hoped there was still enough snow/ice below at that point! It seemed like every day brought another "unexpected" challenge to solve!

If you could look back and choose one moment that will forever stay in your mind, what is it?

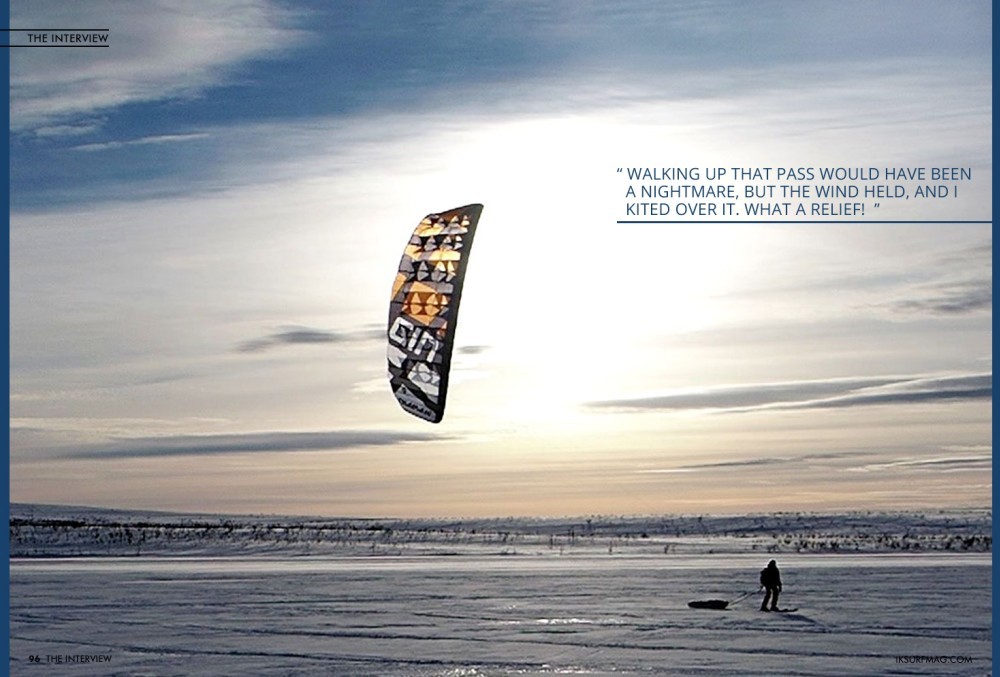

After the fuel leak, I decided to continue north, knowing I was getting deeper into the wilderness, but it was the more "kiteable" option to find an exit point. I was about 100 km away from the exit point and needed some Southern wind. The night had been freezing, the snow was hard, and I started walking in an area that looked like a snowkiting dream spot. But there was no wind.

I walked for 5 hours, pulling the sled, despite the wounds already forming under Whakatau. I knew I needed to get out of there. I was fixated on an ice block on the horizon and thought, "Okay, when I get there, I will stop and eat something". The ice block seemed further and further away until I finally reached it. I stopped and felt a light breeze from the south. I could not believe it. I set up my 12m Shaman, launched, and….. FREEDOM!

Downloop after downloop, I was now moving at 25 km/h instead of the previous 2 km/h walking pace. I desperately needed to go over Juvri Pass to make it to the other side, where I could eventually find snowmobilers that might give me some fuel. Walking up that pass would have been a nightmare, but the wind held, and I kited over it. What a relief! That night, I camped close to a snowmobile track that I eventually found after 10 hours of fighting against the elements.

What was the greatest success?

Completing the traverse and making it out in Maze (Norway) by my own means was probably the greatest success. It had been a wild and tough ride, and Whakatau was wounded but held on pretty well after all.

Did the experience surrounding your injury offer a source of motivation for this incredible expedition?

I was not only doing it for me but for all those whose lives are turned upside down in a matter of seconds. For those who are lying on hospital beds, struggling to see the light at the end of the tunnel, I wanted to give them hope. The hardest part is accepting that the previous version of ourselves will not come back. When people tell you "you will come back stronger", that's bullshit. You probably won't be stronger, but you will be more resilient. If life-changing accidents teach us anything, it is that there is no substitute for hard work. There will be ups and downs, but 1% a day will go a long way. There is still so much to look forward to, and you can feel alive again.

This isn't your first epic adventure, and we know it won't be your last… Any ideas for your next big challenge?

As I said before, this is the way I like to travel. I like to explore and connect with different places, so it will surely not be the last! Kitesurfing, for me, is more than just a sport. Just like my legs, bike or skis, kitesurfing is a tool that allows me to move and explore the beautiful but fragile planet we live on.

This past summer, my sister wanted to experience my way of exploring, and we went to cross Iceland by bike, unsupported. It was a wild experience to share with my sister, although I am not sure she appreciated it as much as I did!!

I have something very special cooking for 2023, something that was already in the back of my mind as I prepared for Lapland. Stay tuned on my Instagram account @nikaadventures. This time, I might find a partner to share the adventure with! Applications are open!

Videos

By Crystal Veness

Editor at IKSURFMAG, Crystal Veness hails from Canada but is based in South Africa. When she isn't busy kitesurfing or reporting on the latest industry news for the mag, she is kicking back somewhere at a windy kite beach or working on creative media projects.