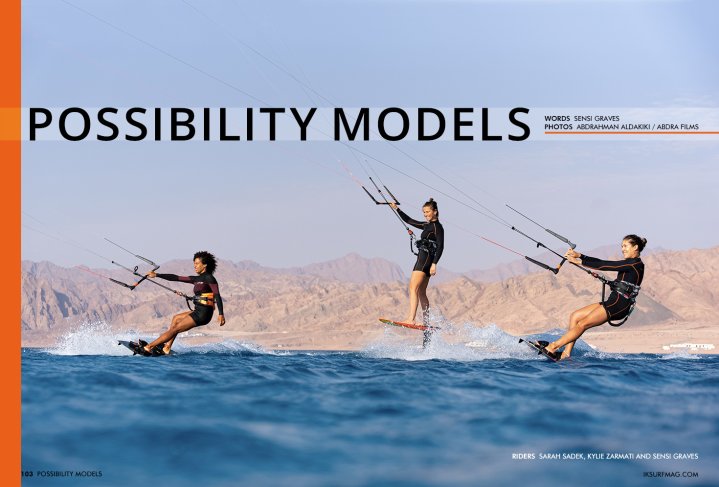

Possibility Models

Issue 103 / Mon 19th Feb, 2024

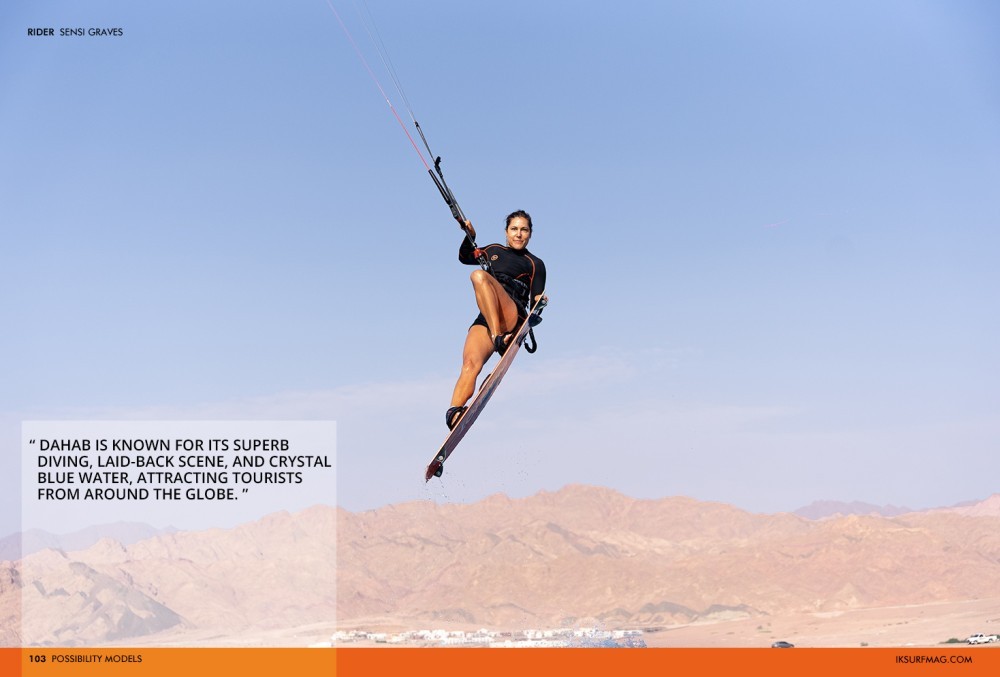

The Blue Lagoon in Dahab is where Sarah Sadek, the first female Egyptian professional kiteboarder, launched onto the scene. Join Sensi Graves and Kylie Zarmati as they visit Sarah on a mission to capture her remarkable story, aiming to challenge societal norms and spotlight the struggles of women in wind sports, particularly within traditional cultures. Their journey is one you won't want to miss! Read it here, exclusively in IKSURFMAG!

The road was bumpy. Our kite bags bounced up and down in the back of the 1996 Isuzu pickup truck, the wind thrashing our hair around our faces. We were jet-lagged, sleep-deprived and pretty anxious to get settled in but happy to be there. Where, you might ask? The Sinai Peninsula of Egypt.

The jagged, rocky, wind-whipped cliffs jutted purposefully from the barren landscape. Craggy and sheer, the stone created a peripheral outline to the sea and sky. It looked otherworldly. And not at all like the location for an international kitesurfing event. Yet, as we rounded the final corner, the fabled blue lagoon came into view, and our nerves started to dissipate. Yep, this was indeed the spot! Kites littered the sky, their colorful profiles making huge arcs against the profoundly clear blue atmosphere.

Kylie Zarmati and I had arrived on location at the famous Blue Lagoon–a picturesque turquoise inlet in Dahab, Egypt–to film with Sarah Sadek–the first female Egyptian professional kiteboarder and the only woman to be competing in this year's Red Bull Winds of Sinai event taking place over the following day. We were there to tell Sarah's story and simultaneously continue the discussion around female representation in a historically male-dominated sport and, from a broader perspective, offer insights into how women have been marginalized in wind sports. Furthermore, we were there to try to change that, to influence our sport, and perhaps, in the depths of our desires, we hoped to change how women are represented in media worldwide.

It was no small goal.

When Kylie and I first submitted our proposal to outdoor brand Cotopaxi to film in Egypt, we knew we had a lot of material to work with. Women are underrepresented in the media across all sports, and kiteboarding, the sport with which we are both considered professional athletes, is no different. Pick up any kiteboarding magazine, scroll through any brand's social media profile or visit any kite companies' website, and you'll find a similar theme–primarily men.

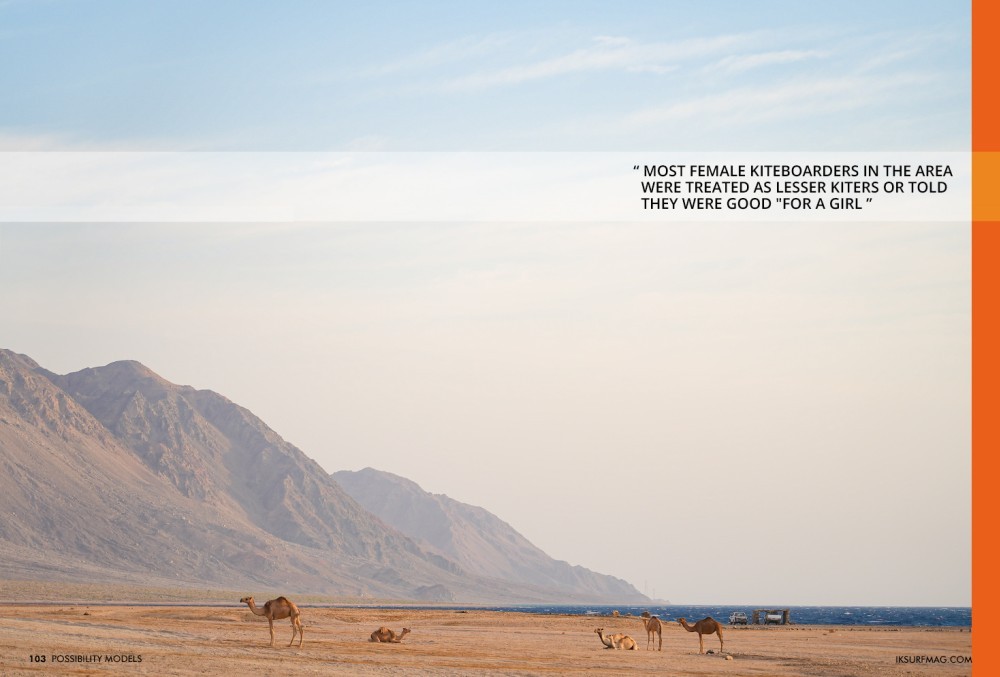

Furthermore, our project was based in Dahab, Egypt, the location of the Bedouin peoples, Arabic-speaking, nomadic peoples of the Middle Eastern Deserts, a microcosm within the broader landscape of two very patriarchal cultures. In Egypt, women have been historically prejudiced against.

We were over the moon when we found out we were awarded the grant to share Sarah Sadek's story. Kylie and I have long dreamed of working on an all-female project within kiteboarding. Kylie has spent the last decade filming social justice pieces for TK. I have spent the last decade traveling around the world as a professional kiteboarder, battling for every dime I make, competing for less prize money than my male counterparts, and, most often, being the only woman on a photoshoot. Ky and I were determined to take matters into our own hands. When we got the call that we won, we simultaneously could hardly believe it and yet, throughout the process and deep in our bones, we knew we would win. We wanted to share more women's stories in kiteboarding. And so did Cotopaxi.

It took us a long time to get to Egypt. From Portland, I flew to Seattle and then to Istanbul, where I had a six-hour layover, then to Sharm El-Sheikh, and finally, we took a one-hour car ride to Dahab. We arrived six hours late, which meant the sun was just beginning to peek out from behind the craggy cliffs as we entered the town. Dahab, a coastal village of about 10,000 people, is located halfway up the Sinai peninsula, a land bridge between Asia and Africa, with the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south. Dahab is known for its superb diving, laid-back scene, and crystal blue water, attracting tourists from around the globe. Most recently, Dahab has become a hotspot for kitesurfing.

Our first day of filming in Dahab was action-packed. We spent the night in a dilapidated hut made from plywood and dried palm fronds clustered around the Blue Lagoon. One lone light bulb hung overhead, and two stained mattresses lay on the floor. But none of that seemed to matter as the sun dawned the next day, and the whole place came alive with athletes, spectators and loads of kiteboarders.

The Winds of Sinai is a yearly competition established in 2022 and produced by Red Bull, one of the few major brands funneling money into kiteboarding events. It is organized by Ismail Hamzawy, whose dream it was to host a big air competition in Egypt with the hopes of it becoming a Big Air Qualifier event. Over recent years, Big Air kiteboarding has emerged as the most attractive discipline in the sport, with jumps reaching over 36 meters in height.

As defined by Sarah, "Big air is a combination of getting as high as possible and doing extreme tricks, that usually include kite loop variations, such as kite loops with rotations, or kite loop board-offs, combinations of both, double and even triple loops. The lower the loop, the more extreme it is. Kiteloops are when you turn your kite around itself, which gives a yank (or pull) to the front while high in the air. This is when all the adrenalin kicks in. It's like being on a rollercoaster, only that you are the one controlling how to rotate or what happens next."

Last year, the event's inaugural year, competitors were mainly locals, but in 2023, there were several international competitors on the water. The competition day started early with the wind building from the north. The Blue Lagoon, and for that matter, the entire Eastern Sinai coastline where Dahab is located, works as a windy location due to the narrow channel that Saudi Arabia and the Sinai peninsula create, forcing a venturi effect as wind funnels down the corridor.

Despite the relative isolation of the Blue Lagoon–spectators have to endure a 30-minute upwind boat ride through rolling swell to even make it to the lagoon–the beaches were filled, and the atmosphere was charged. That's one of the most attractive things about Big Air riding–there's lots of BIG action to take in. It's impressive, explosive and powerful. For the competition, Red Bull set up a mega sound system, podium and an abundance of flags. And then it was on!

Throughout the contest, Sarah was often introduced as the only woman on the water. She showed up in full force and was super impressive to watch. Despite losing both of her heats, you could tell that the entire crowd was impressed and inspired that she was out there. They were eager to support her.

But it didn't start that way. In the early days of Sarah's kiteboarding, she was not welcomed in competitions against men.

Sarah first learned to kiteboard in 2012. Growing up, Sarah would spend all her holidays at the seaside in a town called Ras Sudr, three hours from her home city of Cairo. She and her brother would spend hours playing at the ocean, relaxing with family and enjoying an escape from the arid streets of Cairo.

Kiting started to grow in Egypt in the early 2000s, following in the footsteps of the excellent windsurfing scene that had dominated the region in the 80's and 90's. Ras Sudr was home to a well-known windsurfing school, and Sarah's brother Tarek learned to windsurf while the family vacationed there one season. But Sarah wanted something different. When she got her first glimpse of kiteboarding when she was 15, she immediately wanted to learn–both as a sort of rebellion against what her brother was doing and because it looked like kiters were flying. In 2012, Sarah learned to kite at the Dahab Kitesurfing Center. After that first week, she was hooked and bought her first kite as soon as possible.

At that time, Sarah was still living in Cairo, attending high school and dreaming of kitesurfing. But inconveniently, Dahab and the Red Sea were an eight-hour drive away. Therefore, she could only go on Holidays when she had a few days off from school. Once she graduated, she immediately moved to Dahab for one month after. During her university in Germany, she spent all her summer holidays in Dahab, spending hours on the water with her brother and other windsurfers. It was shortly after that that Sarah set her sights on improving. She was, in fact, not just one of the first female kiteboarders in Dahab but one of the first local kiteboarders. There were always foreigners running kite schools or coming to work as instructors, but only a few Egyptian kiters and almost no Bedouin kiters.

Based on the encouragement of her peers, Sarah started competing in 2018. The first kite competition she entered was dubbed "King of the Lagoon", a kite contest which lasted for 14 years and, before the Winds of Sinai, was heralded as the biggest kiteboarding competition in Egypt. "I was chosen to compete after I showed up and put myself out there as one of the only women. It made me feel seen, and it made me feel really good. I had the chance to show what I can do and that I deserved to be there." says Sarah.

Sarah's progression continued. At the end of 2021, Sarah learned to do a kite loop–a maneuver in kiteboarding that generates a lot of forward power and pull. She continued to put herself out there in contests, winning in 2019: 3rd place at the King of the Lagoon, in 2021: 1st place in the King of the Lagoon, 1st place at Kitemania in Dahab, 1st place at Kitemanina in El Gouna and in 2022: 1st place King of the Lagoon, 1st place Kitemania and competed in the Winds of Sinai for the first time.

Sarah was one of the first female kiteboarders locally, but as Dahab's popularity rose, more women took to the seas. Most female kiteboarders in the area were treated as lesser kiters or told they were good "for a girl". Sarah's experience was a little different. "Because I kiteboarded with a lot of old windsurfers initially, by the time I started kiteboarding with the local men of Dahab, they actually told me I could do it and encouraged me." Yet she was still faced with doubts and discrimination.

As her level started getting better, Sarah wanted to start competing against the men. The level was higher (she was already sweeping the female competitions), the prize money was greater, and Sarah wanted to try her hand and push herself. Initially, she was met with resistance. Some of the men didn't want to compete against a woman. The organizers were worried about the traditional gender roles of the Bedouins–the local tribe of Dahab–as well as how the male competitors would react.

Just 30 years ago, Dahab was an Oasis that didn't mingle with foreigners. The Bedouins are the traditional nomadic tribe that used to travel from the Sinai peninsula to Saudi Arabia and had previously settled as fishermen in the area now known as Dahab. Bedouin peoples speak a different dialect of Arabic, are very connected to nature, and have very traditional (restricted) views of how women and men should exist. To sum it up, women don't kiteboard. They are expected to care for the family, wear Burkas and not engage in sports. While many young male Bedouins have taken to kitesurfing, not a single Bedouin woman was seen at the beach the entire time we were there.

These local customs exacerbated a woman's impact in a male-dominated sport. Not only shouldn't women be on the water to begin with, but it would be a severe loss of face for a man to lose against a woman. In 2022, Sarah beat one of the male competitors during the first year of the Winds of Sinai. Many people started teasing him because he lost to a female competitor. He was very embarrassed. Sarah's response? "I was annoyed–why should it be something funny that they lost to me? I'm a woman, yes, but I'm also good. It shouldn't matter that he lost to a woman".

Women have long been seen as "less than" to men within sports despite overcoming many hurdles. Dealing with a historically patriarchal culture means that women have had to prove their worth and prove their value. Men's sports have had a massive head start.

Let's take a look at a brief history of women's sports in the US (and beyond). In the 1920s, First Lady Lou Hoover proposed that girls' basketball be banned following her appointed committee's investigation into girls playing sports in front of other people, which concludes "that women competing in athletic clothing in front of mixed crowds of men and women was inherently sexual in nature, non educational, and unhealthy," according to Inaugural Ballers: The True Story of the First US Women's Olympic Basketball Team by Andrew Maraniss.

During that same time, the Football Association (FA), the organization in charge of the sport in England, banned women and girls from playing football on any grounds associated with the FA. According to the FA, "the game of football is quite unsuitable for females, and ought not to be encouraged", and it is better for football and other sports to be "exclusively confined to athletics of the stronger sex."

In April 1941, Brazil made it illegal for women to play most sports anywhere. The ban lasted until 1981! Women's sports are ignored. Most schools do not have sports programs for girls.

Finally, Title IX was passed in 1972 in the US, preventing discrimination on the basis of sex for any entity receiving government funding; this affected schools immensely, which now had to provide equal funding for girls' and boys' sports.

Over the years, women have come face to face with first earning the right to play, then earning support and finally earning money for what their male counterparts get paid to do, handsomely. "Women's presence in sport as serious participants dilutes the importance and exclusivity of sport as a training ground for learning about and accepting traditional male gender roles and privileges that their adoption confers on (white, heterosexual) men," Pat Griffin wrote in Strong Women, Deep Closets: Lesbians and Homophobia in Sport. "As a result, women's sports performance is trivialized and marginalized as an inferior version of the 'real thing.'" "What women can learn in athletics contradicts societal messages that encourage girls and women to see themselves as powerless and subordinate," Griffin continued. "Meeting the physical, mental, and emotional challenges in sport is exhilarating. In athletics, women develop a sense of physical competence."

This argument, known as fragile masculinity, proffers that it's men, and men alone, that hold back women in sports. As Lindsy Gibbs writes in her popular Substack Power Plays, "There's a reason why women's sports have been kept on the margins, and it has very little to do with money; it's all about power, and who we're comfortable having it."

Within kiteboarding, there are still fewer women than men on the water. A recent poll suggests women represent just 20% of the kiteboarding market. Brands (run mostly by men) have been using the argument that "there aren't enough women" to justify making women-specific products for years. The question of why there aren't more women in kiteboarding has existed for a long time.

Women in wind sports have long been underrepresented (as outlined above, we are still playing catch up). There have traditionally been more competitions for men. As an example, the competition is called "King of the Air", not Queen of the Air. Having more competitions for women encourages more women and shows what's possible. With more representation comes more opportunity. It's not a question of "when there are more women, we will provide gear/money/opportunity", but "we will provide opportunities to support women now to demonstrate the possibility for upcoming generations of female athletes."

For Sarah, the idea of what could be possible occurred in 2022 when a few high-level international female kiteboarders came to Dahab, among them Natalie Lambrecht and Jasmine Cho, both big air riders competing on the world tour. Seeing other female riders enabled Sarah to see that she was just as good as them and implanted the idea that maybe she could go to some of these international competitions as well. After Jasmine posted a video of Sarah, the team manager for Slingshot Kite saw it and immediately reached out to Sarah to see if she wanted to be a part of the team. She started pursuing a few events, namely the GKA in Tarifa and the BAKL event in Cape Town. Competing against other women on her level gave her more confidence to pursue international competitions.

It is through exposure to people who look like us, doing things we've never seen before, that our worlds are expanded. And that's the importance of showing more women in kiteboarding and in sports–it expands other people's idea of what's possible. We all know the adage, "If you don't see it, you can't believe it". Without showing women in sports, we're creating a dearth of possibility for future generations–men and women alike.

Sarah's story represents what many women have faced within sports–male fragility, low expectations, and judgements. And yet, she is of the generation that can have a real impact on how women are represented, treated, and paid.

Sarah's wish is that more men in Egypt will see what women can do and push their daughters to participate in the sport of kitesurfing. A woman in Egypt might not see a woman training in France or Cape Town, but she would see a local rider. Sarah is serving as her own possibility model. "It's okay for me not to be "as good as the men," but it's important that I get the same opportunities. I just want to encourage women everywhere to try… and to compete!" In Egypt specifically, a lack of women in sports has meant fear around those sports. Fear and being scared limits women. Learning that you can do something just like the guys can gives way more independence for women.

Sarah is holding space for traditional ways to exist but also defying expectations for what it means to be a woman in Egypt. "Happiness comes from having a choice. You feel good. Being happy could result in doing something good. Giving happiness back to community, giving others opportunity." Sarah has a deep respect for the Bedouin culture and the women that participate in it. But she wants women to get the choice. To choose how she spends her life–be it in the traditional, gender-defined way of the Bedouins, or perhaps as something else, and maybe, just maybe, as a kitesurfer.

Videos

By Sensi Graves